From 3D to Banksy: Why Bristol’s Street Art Tops European Walls

By Melissa Chemam | Facebook Page

Banksy is the artist who has rocked the most the global artistic scene since Picasso and Dali. He is the figurehead of street art worldwide. For the most conservative critics, his work is weakened by its ephemeral nature. But one thing is certain for most art historians, graffiti is the greatest revolution that art has known since the second half of the twentieth century, and Banksy is its hero and herald.

With a growing but anonymous success worldwide since 2003, questions about his identity have multiplied. Attempting to unmask Banksy has become an end in itself. But rather than searching whether Banksy could be a certain Robert Banks, Robin Gunningham or Cunningham, Robert Del Naja or even a collective of artists. The most interesting quest around Banksy’s art is about the roots of his career and artistic message.

Once Upon A Time in Bristol…

A month ago, Banksy offered one of his most iconic pieces to the Bristol Museum: ‘A Devolved Parliament’. The move came 10 years after he created it for a unique, free and open-to-all exhibition in the city’s main art gallery: Banksy versus Bristol Museum, opened in the spring 2009.

Since February 2015, I have been exploring Bristol’s artistic scene, meeting and interviewing musicians, rappers, graffiti artists, and engaged Bristolians… I pulled from these exchanges a book, Out of the comfort zone, first published in France in October 2016, and recently published in the UK. And to understand Banksy, according to me, you indeed have to go to Bristol, where he grew up and started in graffiti in the early 1990s.

Banksy’s unconventional creativity come from his hometown precisely, according to me. A multicultural city, marked by a troubled history, slavery and the fight against slavery, a series of riots, and a few waves of migrations from Ireland, Italy and the Caribbean. For Bristol’s creativity did not just emerge in any part of the city, it came from an underground community, especially in St. Paul’s and Montpelier, mainly among immigrants, self-taught rebels and punk fans, during the Thatcher years.

Banksy clearly followed the footsteps of pioneers who opened an underground scene there 15 years before him. And these early writers and taggers made of graffiti an art loaded with messages. Among them, the first of the pioneers was Robert Del Naja, known as a graffiti artist as 3D, who first made graffiti murals in order to create an outdoor artwork set to upset and awaken.

From Bare Walls to the Gallery

Inspired by the writers from the Bronx and Brooklyn, like Futura 2000 and Jean-Michel Basquiat, from 1983, at just 18, this self-taught draughtsman imposed graffiti in Bristol and got noticed rapidly by other graffiti writers based elsewhere in England, then in New York City. 3D, born in 1965 in Brighton, grew in Bristol with a passion for comics, was better at drawing than at maths, and was a passionate music lover from his early years. He switched from The Beatles to punk rock at 11 years old, and was later blown away by a series of EPs of electronica, dub reggae and hip-hop. The Clash were his favourite band and they introduced him to the work of graffiti artist Futura 2000…

Since 1980/82, a few brilliant DJs had emerged in Bristol’s multicultural underground scene, influence by the sound of post-punk, reggae, dub and early hip-hop. They operated in a triptych form: while the DJ mixed discs, they introduced MCs to rap along, breakdancers and graffiti artists, tagging the walls during their performances, illustrating their invitations and flyers, and putting the crews’ names on the city’s walls.

This is what 3D was soon invited to do for the best crew: The Wild Bunch. His early graffiti represented the collective of DJs in the city centre as much as its different hills. Entitled ‘No Great Crime’ or ‘The Day The Law Died’, his bigger murals soon afterwards became a trademark for a new form of graffiti, soon to be rebaptised ‘street art’.

“Young boys took buses from the nearby suburbs just to be able to see 3D’s murals for real, including me and probably Banksy!” remembers Steve Lazarides, later to become Banksy’s manager and a powerful gallery owner.

3D inspired many wanna-be graffiti writers, who started to follow him and compete with him, from the Z-Boys to Pride. D, as he was known by his friends by then, worked closely with the Z-Boys from 1984, and befriended an artist known as Oli T. He also worked alongside with Inkie, aka Tom Bingle, born in 1970 in Scotland but bred in Bristol.

“I was literally trying to follow 3D everywhere,” Inkie told me for my book, when I met with him in 2015. “I even managed to invite myself to his birthday party, ’cause I knew it would be unforgettable! At the time in Bristol, we were still cut off from London,” he added, “we were living in our bubble, so we shared a lot, ideas, projects, good spots, and we helped each other. Everyone knows everyone in the city, or at least your mother or your cousin!”

In 1985, the graffiti scene had been through such a boom in this city that the Arnolfini Art Gallerie decided to host a unique exhibition: Graffiti Art. 3D, at 20 years old, was the main artist involved. This became the first exhibition in Europe devoted to street art. Breakdancers, DJs and the graffiti artists from all over Britain came to a memorable launch evening. Other taggers and writers like Fade, Jaffa, Pride, Goldie, and Bio and Brim, from New York, were among the guests.

That year, 3D also started to write lyrics to augment some of their events. He quickly became one of the best rappers in the club they performed in, The Dug Out.

Counter-Reaction Versus Counterculture

But this revolution on Bristol’s walls was badly seen by the authorities: British police wanted to fight the graffiti phenomenon, like it was doing in the rest of England. Graffiti artists then appropriated themselves the term “vandals”, used to describe their misdeeds. Graffiti became more disturbing than ever, alternative and anti-system.

Arrested twice in 1984 and 1985, condemned to work of general interest, 3D decided to continue his art with commissioned works for pubs, and in other forms, via collage and stencils. He further transformed his art from 1987, evolving towards painting, influenced further by Basquiat and Andy Warhol. He painted walls and canvas inspired by the political era, referencing Margaret Thatcher and the vast unemployment problem. Then he became increasingly dedicated to music, embodying the very strong visual aspect of his new band, Massive Attack.

In 1989, the police found an address book full of names of graffiti writers and launched Operation Anderson to arrest dozens of young people, including Inkie. A gap began to widen between artists who continued their works on the street, and those who reinvented themselves via prints, posters, and illustrations. Instead of letting the scene die, these forms enabled artists to survive, live from their work and thrive beyond the Bristol’s walls. And Bristol was soon ready to strike again.

Banksy’s first steps

In 1985, at the Graffiti Art exhibition, on the sidelines, an 11-year-old child observed 3D at work. He was the future Banksy… A few years later, from 1991, at about 17 years old, he started graffiti writing. The Barton Hill Centre, in East Bristol, was one of the sets of his debuts in graffiti, in the early 1990s. This place helped many artists break through during the Thatcher years; young people could come to play football or practice free bomb design.

Banksy’s first graffiti appeared in Bristol in 1993. He became a member of the DryBreadZ Crew (DBZ) with, among other artists, Kato and Tes. But he didn’t get really known until 1998. That year, he begins to work in the rest of the region, including the largest music festival in England: Glastonbury. There he created with Inkie the work ‘Silent Majority’, outside the Tent devoted to dance music. Inkie was in charge of the lettering. “I painted the truck with Banksy and Lokey for two days at the 1998 Glastonbury Festival,” he told me. “It’s really important because it was probably one of the last times Banksy painted in public and made characters, freehand images, before devoting himself to realisations made mainly with stencils.”

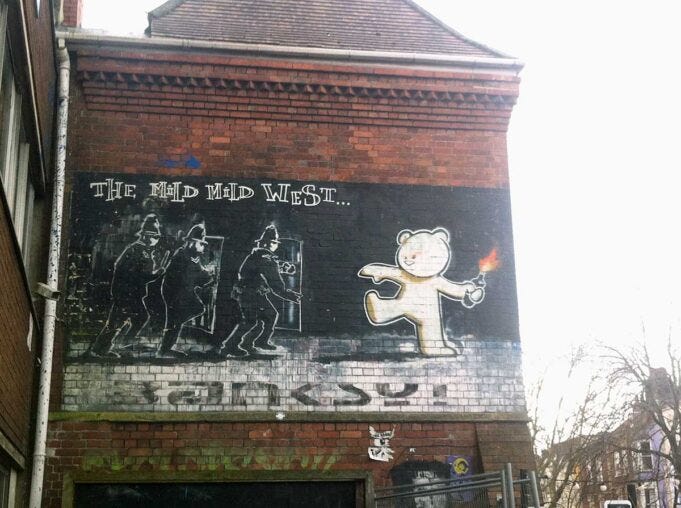

A few months later, Banksy decided to leave Bristol for London and the rest is history. He left to Bristol his most famous local mural: The Mild Mild West in Stokes Croft. Banksy spent a few years in Hackney, switching his art to stencils and written messages, charged with a cynical, dark humour. I would need another article to describe the entire body of his work: rats and monkeys interacting with abstract figures, the formers embodying the stencilled artist, and the later the politicians…

Then he designed his first illegal shows and invented the concept of his ‘Santa’s Ghettos’, unauthorised and surprise exhibitions where one of the first artists he invited to participate was 3D Del Naja.

A Group of Revolutionary Artists

In one of his rare interviews, with the pop culture magazine Swindle in 2006, Banksy himself declared: “When I was about ten years old, a kid called 3D was painting the streets hard. He was the first to bring spray painting to Bristol. I grew up seeing spray paint on the streets way before I ever saw it in a magazine or on a computer.”

3D, by the mid-1990s, had shied away from street art, when it started to lose its anarchist appeal, and transformed his art in order for it to remain thoughtful and insightful, referencing British history like few have, inspired by his city’s very colonial own past. “3D quit painting and formed the band Massive Attack,” Banksy wrote in his book, “which may have been good for him but was a big loss for the city.” But if his legacy is not visible everywhere in Bristol, it had a resonance all through. It inspired a second then a third generation of writers and artists. Unlike other cities like Sheffield, it never lost its passion fro graffiti and dozens of artists have emerged from Bristol since the late 1980s, as well as street art tours and graffiti festivals like Upfest in July.

3D and Banksy have been working together regularly since. For Santa’s Ghettos as well as Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem. From what I understood in my many interviews in Bristol, it was actually 3D who had the idea to stencil Palestinian walls. From 1998, with the worldwide success of Massive Attack’s third album Mezzanine, including fame and long tours, it was obvious that 3D couldn’t spray walls discretely or intensely the same way again. D continued painting, creating artwork for record sleeves and group exhibitions of underground artists.

And Banksy created his own print factory, working on pieces in three dimensions as well, which enabled him to have his first unauthorised exhibitions, in London then in 2006 in Los Angeles. This particular show attracted movies stars and the prices of the pieces on auction went skyrocketing…

All this changed the game for Banksy. And enabled him to keep to stencilling for free, anonymously, in areas each time more surprising. Unlike other street artists, he never lost his stance however, and remains one of the most provocative and political graffiti artists of the world to this day. A touch he owes greatly to his youth in Bristol, and to his primary inspiration, the aforementioned 3D Del Naja.

Melissa Chemam is a writer and journalist, author of a book on Bristol, Massive Attack — Out of the Comfort Zone, published in March 2019 by Tangent Books. It can be found here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Massive-Attack-Out-Comfort-Zone/dp/1910089729 and here: https://www.waterstones.com/book/massive-attack/melissa-chemam/9781910089729

Originally published at http://www.londonstreetartdesign.co.uk on June 21, 2019.